Blue Cut

A blog about computer science and probably other stuff someday. Someone needs to put the other stuff in the description though, but it appears that we might be lazy people.

Written by Aethor Hosted on GitHub Pages — Based on a theme by mattgraham

This post is a (gentle) introduction to 2D region quadtrees quadtrees applied to game development.

You can find a repository with the code of the presented quadtree here. It also contains a demo of the quadtree in action.

prerequisites :

- python basics

- basic datastructures

- basic complexity theory

- recursion

Why Quadtrees ?

Let’s say you are creating a game. A lot of games rely on some sort of physical engine : you probably wan’t your characters to run, dance or shoot lasers according to a set of rules.

A very common task is collision detection : given the set of all entities in a game world, which entities are colliding together ? Usually, bounding boxes are attached to entities, and those are used to determine collisions. A simple bruteforce algorithm might be to check, for each possible pair of bounding boxes, which ones are actually colliding.

for entity in entities:

for other_entity in entities:

if entity is other_entity:

continue

if entity.is_colliding(other_entity):

resolve_collision(entity, other_entity)

However, what happens when you literally have thousands of entities in your game world ? This algorithm checks collision for every pair of bounding boxes. If we have \(n\) game entities, we will have \(\frac{n \times (n - 1)}{2}\) possible pairs, making the algorithm \(O(n^2)\). At scale, this algorithm might start to become unbearably slow, destroying your game and crushing your hopes and dream.

Luckily, there are solutions to this. As in a lot of problems in computer science, the answer lies within the way of storing things : datastructures. If we can find a datastructure that allows us to somehow perform less detection checks, we might still save our game.

One possibility is to use region quadtrees.

What is a Quadtree ?

Quadtrees are special kinds of trees, where each node can have 4 children nodes, each one corresponding to a region of space. We can call those regions North-West, South-West, South-East and North-East (NW, SW, SE, NE).

Each node can be subdivided recursively :

Each terminal node will store the list of world entities present in that region. Here, we’ll store entities belonging in multiples region in all nodes corresponding to those regions at the same time.

Now, let’s come back to our initial problem : collision detection. However, this time, let’s use our quadtree. To detect all collision for a world entity, one only needs to check entities that are in the same regions as the original one !

Coding a Quadtree : an example in python

again, you can find the repository with this example at https://gitlab.com/Aethor/pyquadflow

In this part, we’ll build a very simple quadtree from scratch in python. There are a lot of ways to optimise this code further, but our goal is simplicity here.

(Also, if you are wondering, functions with a trailing underscore (like insert_) indicate a side effect (which means the tree will be modified by the function). It is only a personal convention that I impose to myself (but I believe PyTorch also does so).)

Pre-requisite : rectangles

To keep things simple, we will only work with basic rectangles. Let’s start by creating a simple Rectangle class that we will use throughout this example :

class Rectangle:

def __init__(self, x: float, y: float, width: float, height: float):

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.width = width

self.height = height

def is_colliding(self, other: Rectangle) -> bool:

return (

self.x < other.x + other.width

and self.x + self.width > other.x

and self.y < other.y + other.height

and self.height + self.y > other.y

)

Quadtree basics

We can say that our quadtree has a rectangle to represent its underlying space (self.region here). it also has a set of entities, which are the stored game entities (here, a bunch of rectangles) and, potentially, a set of children.

def __init__(self, region: Rectangle, max_entities_nb: int, max_depth: int):

self.entities: Set[Rectangle] = set()

self.children: Optional[List[Quadtree]] = None

self.region = region

self.max_entities_nb = max_entities_nb

self.max_depth = max_depth

By convention we set the children field to None when the node has no children. This allows us to have the following utility function to check if the current node is a leaf node :

def is_leaf(self):

return self.children is None

The self.max_entities_nb field is here to have a condition on the tree splitting : When too much entities are on the current node, we will split our trees into four children.

Lastly, the self.max_depth field prevents the tree from splitting indefinitely, which might happen when the size of the smallest region of the quadtree is smaller than a game entity.

Now, we can start implementing some methods of our quadtree !

Insertion

As usual with trees, we can implement everything using recursion. A common pattern in trees is that we wan’t to know wether we’re in a leaf node or not (hence our is_leaf() function). When we are in a leaf node, we perform a terminal action, while when we’re not, we launch the function recursively on the node’s children. Here is our insertion function :

def insert_(self, rectangle: Rectangle):

if self.is_leaf():

self.entities.add(rectangle)

if len(self.entities) > self.max_entities_nb and self.max_depth > 0:

self.split_()

return

for child in self.children:

if child.region.is_colliding(rectangle):

child.insert_(rectangle)

When inserting, both cases are pretty self-explanatory :

- If we are not in a leaf node, we call insert_ on every child intersecting with the entity we want to insert. The fact that we only recursively launch the function on intersecting children means we optimize computations by ignoring irrelevant regions of space.

- If we are in a terminal node, we already know that the given entity should be inserted : we simply add it to the node’s set of entities. However, there is a catch : if the number of entities is too big in this node (see our

max_entities_nbfield !), we must split our tree in four ! This involves creating four new children, and assigning them to ourchildrenfield.

def split_(self):

child_width = self.region.width / 2

child_height = self.region.height / 2

possible_positions = [

(self.region.x, self.region.y),

(self.region.x, self.region.y + child_height),

(self.region.x + child_width, self.region.y + child_height),

(self.region.x + child_width, self.region.y),

]

self.children = [

Quadtree(

Rectangle(x, y, child_width, child_height),

self.max_entities_nb,

self.max_depth - 1,

)

for x, y in possible_positions

]

for entity in self.entities:

for child in self.children:

if child.region.is_colliding(entity):

child.insert_(entity)

self.entities = set()

Note that an entity can be inserted in different regions at the same time : in fact, it is inserted in all terminal regions colliding with it.

Deletion

Deleting entities in a quadtree might be tricky, because we have to make sure to delete a node children when they contain less entities that max_entities_nb together. We make use of the same patterns we observed when designing insert_() :

def delete_(self, rectangle: Rectangle):

if self.is_leaf():

if rectangle in self.entities:

self.entities.remove(rectangle)

return

for child in self.children:

if child.region.is_colliding(rectangle):

child.delete_(rectangle)

nested_entities_nb = sum([len(child.get_entities()) for child in self.children])

if nested_entities_nb <= self.max_entities_nb:

self.entities = self.get_entities()

self.children = None

Again, we have two cases :

- If we are not in a leaf node, we must launch recursively our function on intersecting children. After that, we must check that the number of entities in the node’s children is still greater that

max_entities_nb. If it’s not the case, we must update the tree by deleting children nodes. - In a leaf node, we simply remove the input entity

Collisions

We said it in the introduction : quadtrees can help you (among other things) reduce the number of collision computations. The following function determines if a specific rectangle is colliding with something in the game world :

def is_rectangle_colliding(self, rectangle: Rectange) -> bool:

if self.is_leaf():

for entity in self.entities:

if not entity is rectangle and entity.is_colliding(rectangle):

return True

return False

for child in self.children:

if child.region.is_colliding(rectangle) and child.is_rectangle_colliding(rectangle):

return True

return False

Movement

There is different ways we can achieve movement in a quadtree. The main problem is that you might need to update the tree when an entity leaves or enter a new region. We can opt for a simple (probably not optimal) option, and simply remove and insert our entity again after its position changed :

def move_(self, rectangle: Rectangle, position: Tuple[float]):

self.delete_(rectangle)

rectangle.x = position[0]

rectangle.y = position[1]

self.insert_(rectangle)

Performance Test

To validate that our quadtree helps reducing the number of collisions when our number of game entities is high, I created a simple demo (see demo.py at https://gitlab.com/Aethor/pyquadflow if you want to try it out by yourself). It works as follows :

- When left-clicking, the demo will add a rectangle to the displayed quadtree using the

insert_method - At creation, rectangles are assigned a random speed vector. Each frame, rectangles will be moved according to this speed vector using our

move_()function. Rectangle also bounces on the edge of the quadtree root region - Each frame, the demo will check for collisions using our

is_rectange_colliding()function. Any rectangle colliding with another rectangle will be shown in red instead of black

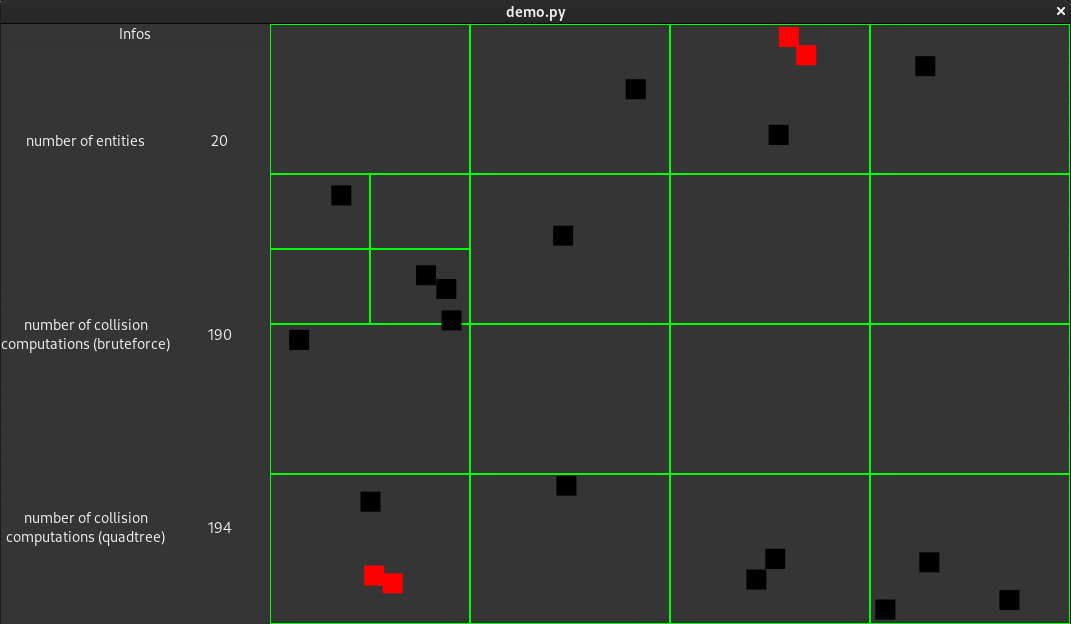

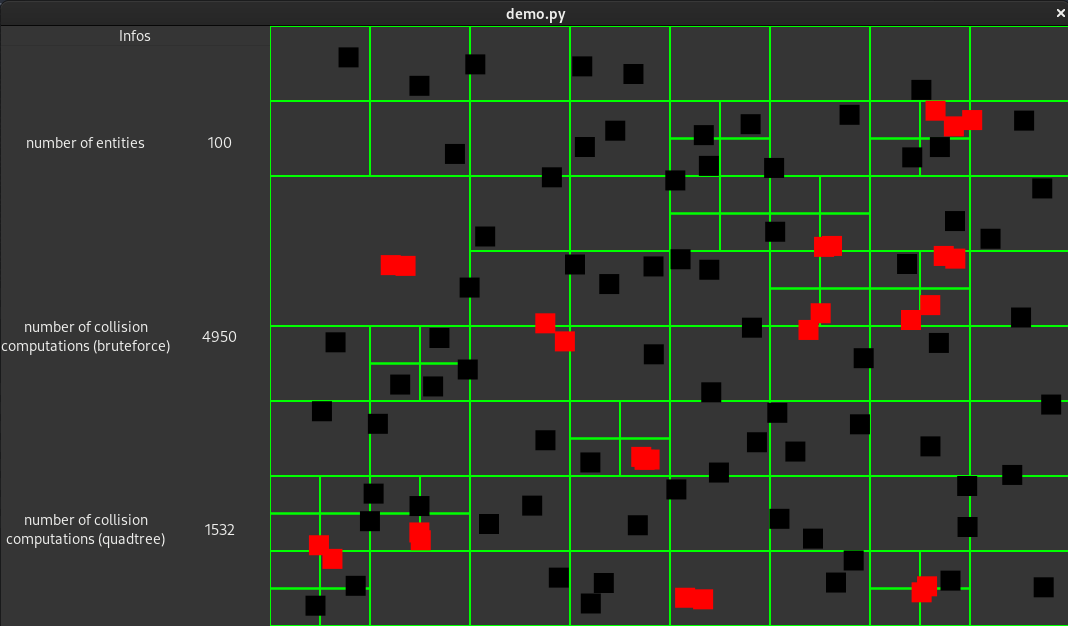

There are two collision counters at the left of the interface :

- The bruteforce counter shows the theoritical number of collision calls when using the bruteforce function (\(\frac{n (n - 1)}{2}\))

- The quadtree counter shows the actual number of calls of the

is_colliding()function of theRectangleclass when using the quadtree

With a small number of entities, our quadtree gives us no gain :

However, as the number of entities progresses, our quadtree quickly starts to reduce the number of collision computations :

Going further

Optimising storage

In our implementation, you can notice that we store game entities in leaf nodes’ sets. In practice, this might be a bad idea. A Python set, in terms of storage, comes with some base fields. Consider running :

>>> import sys

>>> sys.getsizeof(set())

216

As you can see, an empty set comes with 216 bytes (!) of allocated storage. If your tree is deep, you can quickly store a lot of sets, which can add up to a lot of memory. Depending on your needs, a better option would be to store entities in a continuous array global for the tree, where elements are only referenced by leaf nodes using singular values.

Barnes-Hut approximation

Here, we only showed a simple example involving collisions. However, in most physical simulations, one will usually have to compute the action of some forces on all entities. One common force is of course gravity, but gravity can be costly to compute. To compute the gravitational force applied to a single entity, one needs to refer to the mass of all other entities of the system ! Hence, gravity computation is of complexity \(O(n^2)\).

Luckily, there exist a way to approximate gravity computation using quadtrees : the Barnes-Hut approximation [3].

The idea is simple. Let’s look at the classic gravity force formula between two objects :

\[F = G \frac{m_{1} m_{2}}{r^{2}}\]Where :

- \(G\) is the gravitational constant

- \(m_1\) is the mass of the first object

- \(m_2\) is the mass of the second object

- \(r\) is the distance between the two objects

From this formula, it is trivial to see that the further away two objects are, the lower the gravitational force between them. It naturally follows that when you are trying to compute the global gravitational force for an object in a world with a lot of objects, farther objects are less important for the precision of the simulation.

To decrease the number of computations, one could simply ignore distant objects, keeping only a certain number of close objects involved. However, The Barnes-Hut approximation is a bit more clever.

Let’s suppose we have a quadtree. Instead of ignoring distant objects, for distant quadtree nodes, we can compute a global mass for the node with the objects it contains, and treat it as a big object. Therefore, objects in the same sector only need one computation, at the cost of a bit of precision.

When objects move, the tree might need some updating however : when an object moves from one node to another, the sum of masses of both nodes should be computed again.

Compression with Quadtrees

Quadtrees could be used for compression. To give an intuition, we will talk about a simple application on images. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll only consider black and white images.

At the simplest level, images are grids of pixels. If we consider a black and white image, we could for example create an image where each pixel contains a value between 0 and 255 (the reason being, it fits nicely on a byte), 0 being absolute black while 255 being absolute white.

Now, we can certainly take this grid and store it into a quadtree, by making each pixel into a leaf node.

But what does this have to do with compression ? Well, for example, we could remove leaf nodes, and set the parent nodes values to the mean of the children nodes values. Depending on the level of compression we want to achieve, we could repeat this process several times :

![]()

Of course, this is an extremely simplified and naive idea, but it is an example on using a quadtree for compression (with loss of information).

Using other structures

There are actually a lot of datastructures you can use for your spatial needs ! Depending on your use case, you might prefer kd-trees, R-trees, VP-trees, different types of grids…

References

- [1] Finkel, R. A. and J. L. Bentley. Quad trees: a data structure for retrieval on composite keys. Acta Informatica. 4, pp. 1-9. 1974.

- [2] Dinesh P. Mehta and Sartaj Sahni. Handbook Of Data Structures And Applications. Chapman & Hall/CRC. 2004.

- [3] Barnes J. and Hut P.. A Hierarchical \(O(N log(N))\) force-calculation algorithm. Nature. 234 (4) : 446-449. 1986.